Suspension Is No Substitute for Justice: SC Reasserts the Narrow Scope of Bail After Murder Convictions

- M.R Mishra

- Dec 19, 2025

- 3 min read

The Supreme Court’s decision in this case , revisits the uneasy balance between personal liberty and the gravity of criminal culpability once a conviction has been recorded.

Setting aside the Patna High Court’s orders suspending sentence and granting bail to two convicts sentenced to life imprisonment for murder, the Court has sent out a clear message: suspension of sentence in cases under Section 302 read with Section 149 of the Indian Penal Code cannot be treated as a routine interim relief.

What's The Matter?

The appeal arose from a brutal incident that took place inside a village temple, where Krishna Behari Upadhyay was shot dead in the presence of his son, the complainant.

The Sessions Court, after appreciation of ocular and medical evidence, convicted multiple accused, including Sheo Narayan Mahto and his son Rajesh Mahto, under Section 302/149 IPC and the Arms Act, sentencing them to life imprisonment.

During pendency of their criminal appeals, the Patna High Court suspended their sentences and released them on bail, largely on two considerations: that their role was limited to instigation and that there were procedural aspects such as a three-day delay in forwarding the FIR to the Magistrate and non-production of the original inquest report.

The Supreme Court found this approach legally unsustainable.

Speaking through Justice N.V. Anjaria, the Court emphasised that once a conviction is recorded after a full-fledged trial, the presumption of innocence ceases to operate.

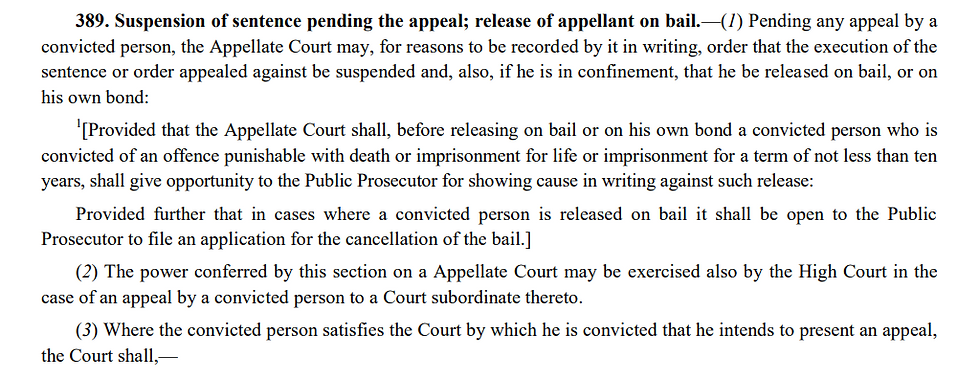

The power under Section 389 of the Code of Criminal Procedure to suspend sentence pending appeal is qualitatively different from the power to grant bail during trial. It is not an extension of the pre-conviction liberty regime but an exception that must be exercised with circumspection, especially where the conviction is for murder and the sentence is life imprisonment.

The Court was particularly critical of the High Court’s reliance on procedural factors unrelated to the core evidentiary findings of guilt.

A marginal delay in forwarding the FIR or the absence of an original inquest report, it held, had no rational bearing on the credibility of the prosecution case which had already been tested and accepted by the trial court.

At the stage of Section 389, an appellate court is not expected to reappreciate evidence or search for minor infirmities, unless the convict is able to demonstrate a glaring or palpable error that strikes at the root of the conviction itself.

Equally significant is the Court’s treatment of the argument that the convicts were mere “instigators”. The judgment underscores that in cases of unlawful assembly attracting Section 149 IPC, culpability is not confined to the hand that fires the fatal shot.

The presence of the accused at the scene, armed with firearms, actively exhorting the killing, and fleeing thereafter, was sufficient to attribute grave participation in the crime.

The Court noted that both convicts were armed and part of the collective assault inside a sacred space, factors which only heightened the seriousness of the offence rather than mitigating it.

By cancelling the suspension of sentence and directing the convicts to surrender, the Supreme Court has reaffirmed long-settled principles laid down in decisions such as State of Haryana v. Hasmat, Shakuntala Shukla v. State of Uttar Pradesh and Omprakash Sahni v. Jai Shankar Chaudhary.

The consistent thread running through these authorities is that suspension of sentence in murder cases is permissible only in exceptional circumstances, and parity with a co-accused who has erroneously been granted bail cannot itself be a ground for extending the same benefit.

The decision thus stands as a reaffirmation that Section 389 CrPC is an exception, not the rule, and that life imprisonment for murder carries with it a presumption of continued custody unless compelling and extraordinary reasons dictate otherwise.

Comments